First, a caveat. I used to work on John Lewis, ostensibly as a Comms Planner but later as an “in effect” Marketing Strategist and Consultant. I have great affection for the business but I’m also (and was) clear sighted about the problems that had been building up for several years before the recent visible financial troubles. I’ve been out of the business for over a year now. December 2019 was the last time i was at Head Office but whilst i attended meetings in 2020 they were under the auspices of the ‘intermediary’ restructure instigated prior to Dame Sharon White taking over and implementing her vision.

Anyway on to the update and it’s an interesting one. Part of this is because as a private business there is no nessecity for the John Lewis partnership to publish this sort of information. One of the first casualties of this was the weekly sales results they used to publish. It was a fascinating bellwether for the business but also a wonderful source of useful data that i imagine analysts at all the competition (what’s left of it) used. That said we still get the twice yearly updates and the unaudited full years have just dropped. There have been changes to how the data is structured and the emergence of a little more corporate obfuscation which i would suggest is linked to Dame Sharons background as an economist. Also it makes sense. Why give your competition the financial keys? Reading a few of the summaries yesterday (i don’t work Thursdays) and reading the announcement today, I’m caught by how many have failed to point out some of (what i would see as) the salient points. So into that….

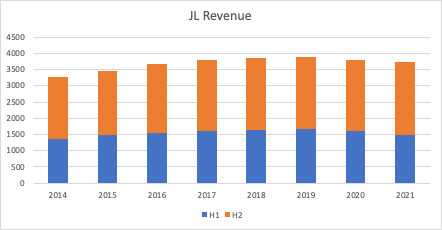

To start with its worth looking at the revenue figures. When people say that high street brands are dead its worth looking at the amount of money these so called “failing” businesses are actually doing. In John Lewis’ case, they still managed to post est. £3.7bn which i’ve got as around 1% down YoY . It should be noted that this includes an extra week of trading but we’re still talking about a huge business from a consumer perspective. Also worth noting that the L4L is posted at 0%.

To put this into context I estimated that Debenhams was a £1bn business last year, whilst i estimated that M&S would do £1.7bn (discounting for a successful Xmas) and Next has suggested its profit would be circa 2/3rds of total which when applying a simple scale up (plus Covid cost estimates) suggests around £3bn. So John Lewis pull in a lot of cash and on this benchmark they’ve done/doing very well!

On the Waitrose side its been decent too with a 10% increase in revenue to £7.044bn. As a flavour for the rest of the market its remarkably consistent and whilst most of these results aren’t full year and are therefore extrapolations they are fairly uniform and paint a good picture for Waitrose. When i say uniform, we’ve seen the following at Tesco (8.5%), Sainsbury (c8%), Morrisons (8.6%) and CO-OP food (8.8%)….

I’ve charted the figures up over the last few years to give you a sense of what’s happening –

The next step of this analysis jumps into how this actually converts into profit though. Historically i’ve used Operating Profit excluding exceptional items and the bonus (and tax) as the ultimate figure. Exceptional items are a “funny one” although historically they’ve not really appeared all that often, although in recent years it seems like its been open season. 2020 was when it started to get complicated though.

There are two reasons for this. One is strategic whilst the other is legislative. The legislative one is related to the value of leases (IFRS 16) and therefore there is an argument that we should go back through the numbers and estimate the historic “book value” that we’re seeing. This isn’t going to happen. Therefore it can only really be seen in the new figures. This creates a bit of an apple and pears situation, not idea but unvoidable it seems. JLP flag this in their recent report and there is a (£53m) effect (page 7) and its all against the JL estate, rather than Waitrose.

The other element is strategic and there are lots to this one. Firstly there are the emergence of group efficiencies which mean that going forward we won’t be able to view segmental Operating profit (it will be one figure) which applies one level of opaqueness to separating the two businesses. Secondly we had some whopping exceptionals. The first is a £249m addition caused by closing the final salary pension scheme. I’m not an accountant but this is booked against 2020 in its entirity. This isn’t real money as such and the benefit will be felt for years to come in increments rather than all at once. There is also the presence of a (£63m) amount which is related to strategic operations and redundancies AND a (£110.3m) write down of the John Lewis estate due to the shift to online business (we saw this again this year). You can see why the pension scheme amount is useful. It basically allowed JLP to add £107.4m into the year as exceptional. Without this we’re talking about a (£150m) amount in a year where the profit before tax was £146m. (see all this here). So whilst 2020 looked decent, we’re already on less steady ground, although the cash generative nature of the business is still strong with £753m generated with £600m on the balance sheet.

One of the big changes to JLP reporting is that they no longer provide segmental breakdown at a profit level (few public businesses do) from 2020/21 onwards. We have historic data so we can work with these margins to estimate though. This is where it gets a bit more interesting. For the first iteration i’ve left off 2021 as there is a lot more going on.

A few things of note here (as i’ve split the data by Half too) is that John Lewis are truly a H2 brand. All the profit now comes from H2 and most of this will come from the golden quarter. Everyone sees them as a Christmas brand and this is what that looks like. Waitrose on the other hand (bar 2018 when there was a price hike and Waitrose refused to pass over the price rises to consumers) are clearly moving back to where they were and seem to be well positioned.

So what about 2021. How do we estimate that? The best place to start is H1. Now the headline for H1 was a £580m loss due to a write down (we’ll saw this again in the full year results naturally). Stepping back to the figure that JLP use before exceptionals gives us some insight. This totalled -£55m. So prior to the huge write down they were making a not insignificant loss as a group. Looking back at prior years we can see that Waitrose has cross subsidised the John Lewis business before but not this year. With this in mind we can estimate the contribution to this loss by brand. We know that Waitrose was up around 10% in revenue terms. Taking the 2020 H1 ratio between Revenue and Net profit of 34.8% we can apply this to the 2021 figure to give us our estimate. We can also then simply work out the differential between this and the -£55m. This gives us +£128m for Waitrose (£3.7bn revenue at 30% conversion) and therefore a figure of (£183m) for John Lewis. That is a BIG loss in H1 and also includes some £50m from the Govt, for furlough.

Then we come to the full year view. Again, the comparison is difficult so assumptions have been made but we can estimate that Waitrose made £104m in H2 on revenue of £3.3bn. This looks like this –

What does that mean for the John Lewis brand? Well bearing in mind that the total group profit for the year was £131m we can run through the following calculation. Waitrose contributed est. £232m to the pot in the year. We previously suggested that the H1 loss to John Lewis was (£182m) so simple maths says that the John Lewis total year loss was (£101m) which means that H2 was actually positive at £81m. BUT, £190m of this was government cash. There has been much debate about whether JLP should hand back some of the Govt. money as Waitrose benefitted disproportionately (remember its up 10% vs other brands at 8.5%) and this is why they won’t. Essentially the group comes in at (£59m) without this. Then you add in the write down of the estate on top (it halved in value) of (£648m) and you can see where the headlines came from. Without government help the business would have written an £707m loss. Obviously the huge caveat is that Im not a financial analyst so i can’t absolutely guarantee these figures are perfect. You’ve also got an increase in cash generation to £832m.

OK. So why does someone with a background in marketing look at all this stuff. Well, i’m interested for a start. That and by following the money you understand the business better. It also allows you to disabuse yourself of narratives.

So what are the implications for all of this? It’s clear that the business is inefficient. John Lewis especially has struggled to convert good revenue levels into profit. There is too much cost and I would imagine the closures represent stores which have struggled to provide any sort of profit. Too big, too expensive, not enough demand. The closure of the bullring store in Birmingham is telling. 5 years old and flagship status (until Westfield), paints a very poor picture of the historic decision making processes. Like M&S before them, closing these stores will benefit the business hugely BUT; are JLP missing a trick? It’s last man standing now (Debs and HoF having “disappeared”) and there will surely still be a place for city centre malls, especially when John Lewis have never really had the large scale footprint of the others i.e. more manageable. This puts them in an enormously powerful position to renegotiate rents and leases as there is no-one else. The business is also still driving significant demand i.e. revenue as well. People still buy from John Lewis and even if that’s via the website, its a remarkable strength especially relative to their competitors.

So where does marketing come in? The John Lewis brand is very well known. It’s CEP (category entry point) is clearly Xmas but it has to be more than that really, they can’t keep carrying H1 as a passenger. The issue is more about the future and the Prime Ministers partner Carrie Symonds was recently quoted as suggesting that she wanted to get rid of “the John Lewis furniture nightmare” is probably an accurate representation of what many believe to be behind the John Lewis doors. Expensive (relatively) but also quite beige. Black Friday is now a major electronic goods period but essentially acts as a black hole before Xmas and whilst the returns policy is probably what drives demand, as cohorts age the awareness of this will drop (and electronics are hugely online and price sensitive as a result, not a good place to hang their hat). Clothing is an odd fellow within JLP. They have lots of brands (their own and 3rd parties) but there is no one real style or reason. You know why you buy at M&S but do you know why you’d buy at John Lewis? What are people buying when they go in? Could John Lewis have bought Jaeger for example? If fashion is to continue then a clear reason needs to be built. Brilliant basics has been a clarion call for many in fashion retail for years but this is a very competitive area. A Best of British position, could be an interesting platform through which to create distinction and support young DTC companies that are desperate to increase their distribution (acquisition in this space could also be investigated…)

The official documentation suggests a reinvigorated focus on Nursery and Home. It does feel as though there is a John Lewis effect when you start a family. You’re stressed enough as it is and therefore you benefit from an “all in one” shop, it’s a shame that when i bought it up buying up the UK Mothercare franchise there wasn’t the decision making apparatus in place. Ultimately JL is a lifestage brand and leveraging this for new cohorts would be a good idea whilst refreshing the older groups who have lost their lustre. You hit the John Lewis age range as a 30 something and then you’re in….

The suggestion of smaller more accessible stores is interesting but leveraging Waitrose is a better idea and should be prioritised. Small stores would only work as specialists and we already know from closures that the home-alone model doesn’t work. As to financial services and rentals, this is where the direction veers a bit. John Lewis Finance is profitable but it’s not distinctive in market. There are suggestions of new products being released but they’re playing with commodities in home insurance. Its not a game changer. Becoming a Peabody trust for the modern world is a fun idea but again this is a whole new unfulfilled area and the point with Peabody is that its a charity and therefore not cash generative, what’s the benefit to John Lewis here? It all feels as though the answer is being sought outside retail. Thats quite a leap for a retailer who is currently struggling to get the basics right (and by basics i mean generating profit from large revenue streams).

As for Waitrose. It seems like its on a reasonable course. All the grocers have benefitted and there was certainly a fortunate element to Covid and the handover from Ocado which forced immediate scale up. The issue with Waitrose is long standing and thats the quality/price differential. As value retailers increase their quality the gap reduces whilst the prices remain the same. You’ve then also got the “return to local” & “farmers market” elements that push against its positioning as the place for quality food.

The relationship between JL and Waitrose is also interesting. If you look at Sainsburys and Argos (plus multiple other brands) you can see a strategy in place that is founded on monetising shop floor space. Tesco and Morrisons are vertically integrated whilst Co-Op are local. Lidl and Aldi are opening lots of stores (and running up lots of debt). So how can the JLP work better together? Operationally there are clearly cost benefits that we’ve mentioned previously. The horizontal integration approach of Sainsburys seems to be an easy win but even Sainsbury’s had to try to merge with ASDA to supplicate the city (and that failed too) but here is the rub. JLP doesn’t have to profit maximise. It only has to keep running in the mid term and keep its partners happy in the short term. The £400m target for profit is just over half what Next does in a normal year and JLP is twice the size when you roll the two businesses together. There does seem to be a lot of cost within the business as mentioned but if this cost is used to provide elevated services then there is no reason why it cannot return to its thriving state. This is the key. It may not have to be efficient but it must invest the efficiency gap into something that consumers want and value, that could be pricing (which is alluded too), quality of product or simply expensive signalling. Its worth remembering that Selfridges wrote a £80m op profit last year from a handful of stores. Harrods does very well too, whilst Frasers is going all in on Flannels. Luxury (or mass premium in the John Lewis world) is something people will pay for however first of all your have to fix the inefficiencies in the operations and that’s easier said than done. The forward guidance of £800m investment does sound interesting though! Let’s just hope it’s spent more wisely than the £35m spent on John Lewis store in Birmingham.